Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Placetest: New Poundbury

Its Royal patron makes Poundbury the focus of much attention, and the development is not even finished yet. Anthropologist Caroline Bennett visits and speaks to locals with exclusive photography by John Sturrock

Caroline Bennett is a socio-cultural anthropologist, whose work addresses issues of conflict and violence.

“There are mythical beliefs that Poundbury is somehow different; that life works differently here, but it’s a normal place. Children go to school. People fall over and break their legs. It’s like anywhere else," says Peter Noble, a long-term resident of the area.

Mythological is a good term for Poundbury. The development has a lot of attention for a development that won’t complete until 2026, primarily because of its royal patron, King Charles III.

Until he handed the Duchy of Cornwall over to Prince William last year, Charles owned the land Poundbury sits on. He also oversaw the design and set the ambition for Poundbury as one of the first developments in the UK to follow the principles of the New Urbanism, which sought to engender an urban renaissance that would return identity and community to new developments. Construction started in 1993.

The location of Poundbury has long been part of mythological England. In the 19th century, Thomas Hardy was resident in Dorchester. Many of the novels he wrote were based in Wessex - a "magical, literary landscape" as Alan Bennett described it, that blurred the lines between reality and imagination to create a landscape of "ideal Englishness" - timeless, rural, traditional, and hierarchically organised. Industrialisation and modernisation were part of this, but rather a negative part - one that had created an irreversible loss of contact with the past and thereby identity.

Interesting then, that Hardy’s fictional Casterbridge is in reality Dorchester, including Poundbury, an experimental urban extension of the New Villages Movement.

Past and present are united and intertwined with cultural meanings that blur temporal boundaries. Having been built in a short amount of time, this blurring of timespan makes it challenging for Poundbury to create community with a sense of belonging and place

The development did not emerge from Charles’ imagination alone. In 1987, when West Dorset District Council needed space to house its rapidly expanding population, it identified Poundbury as the ideal site: 160 hectares (400 acres) of mostly agricultural land owned by the Duchy of Cornwall. This was the beginning of New Poundbury.

While technically an urban extension of Dorchester, Poundbury’s identity is unclear. Correctly named New Poundbury (because Old Poundbury, an existing community with a long and continuously inhabited past, also exists in the area), some call Poundbury a village, identifying it as having its own community and identity; others are adamant it’s simply an extension of Dorchester.

In 1988, Charles invited Krier to design Poundbury and create its masterplan; one that is still rigorously followed today. To ensure its "faithful realisation", Krier invited his long-time collaborator, Duany to create Poundbury’s urban building code, which was incorporated into the plan.

Emma Mumford, an entrepreneur with her own wellness business, moved to Poundbury in 2015, and says its sense of place has grown. "When I first moved here, it definitely felt like an extension’’ she says. "Now it feels like its own village, I guess. Maybe town? I don’t really know what you’d call it. But it feels like a community, and I think it’s grown into its own identity."

Arriving on a Sunday afternoon, as an outsider, Poundbury feels like a different place from Dorchester. I walked from the train station and followed the main route, past the hospital, along a road where the housing density gradually reduced, until I came to a set of roundabouts where a signboard presented a large map of Poundbury. Smaller signposts, marked with the crest of the Duchy of Cornwall, directed me to different parts. It was clear that I had arrived and the distinction was marked.

Clare Tarling, who lives in Dorchester and works in Poundbury, also notes the distinction. "It doesn’t blend,” she says. "You’re in old Dorchester and then suddenly you’re in Poundbury. It’s not like it meshes. Down by the bus stops at the end of The Great Field: that’s where Dorchester finishes and Poundbury starts. It’s very obvious."

Whether it’s an extension of Dorchester or its own locality in people’s minds, arriving there, it feels like a separate place.

Developing Poundbury

In the 1980s, a new architectural movement known as New Urbanism was beginning to emerge in the United States. New Urbanism aimed to build sustainable communities by creating areas where living, working, and leisure were interconnected and most everyday activities could be conducted on foot. Such design was based on traditional neighbourhood structures, based on walkability and connectivity, mixed-use and diversity of housing, businesses and leisure, and sustainable development aiming to improve quality of life. The movement found champions in the United States among architects such as Leon Krier and Andres Duany. In the UK, Charles then Prince of Wales was a champion, too.

In 1989, Charles published A Vision of Britain: A Personal View of Architecture. In it, he outlined 10 principles of architectural design, principles he defined as "sensible and widely-agreed rules, saying what people can and what they cannot do". His premise was that architects should serve both aesthetic and practical needs of ordinary people, and that architecture should harmonise with its surroundings. He believed such urbanism would re-establish "pride" in place.

They disliked the kind of urban development represented by identikit low-density housing separated from places of business and leisure, leading to a reliance on cars and creating divisions between people and places

Krier, Duany and Charles were all self-identified traditionalists, who bemoaned what they saw as the horrors of 20th-century architecture and its effects on the community. In particular, they disliked the kind of urban development represented by identikit low-density housing separated from places of business and leisure, leading to a reliance on cars and creating divisions between people and places. When West Dorset Council approached the Duchy of Cornwall to ask for space for its urban extension, the possibility of putting these theories into practice was presented.

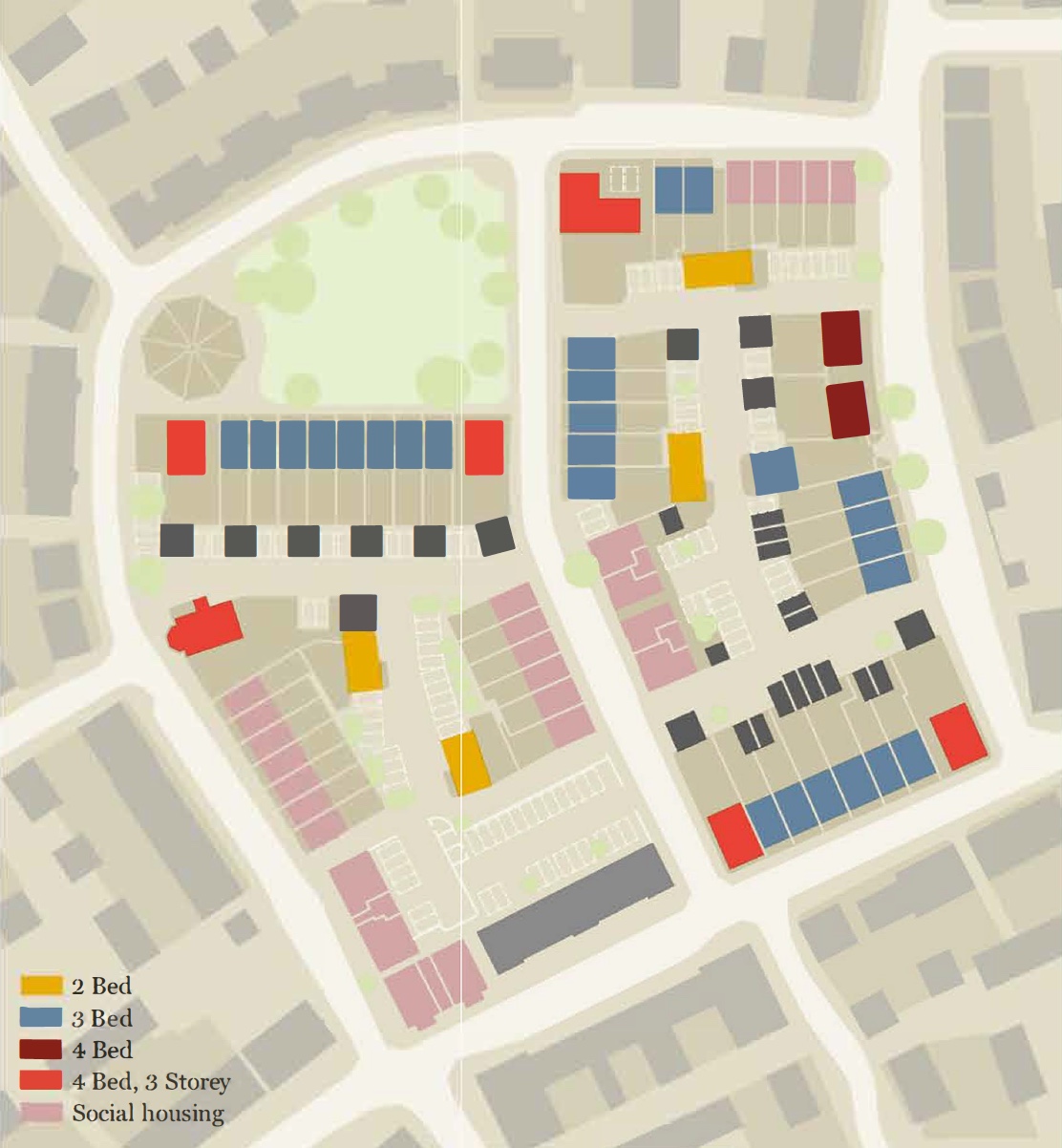

In 1988, Charles invited Krier to design Poundbury and create its masterplan; one that is still rigorously followed today. To ensure its "faithful realisation", Krier invited his long-time collaborator, Duany to create Poundbury’s urban building code, which was incorporated into the plan. Poundbury reflects four key principles, as outlined on its website: architecture of place, creating beauty and reflecting local character and identity; integrated affordable housing throughout the development and indistinguishable from private housing; mixed use - homes, public amenities, retail and other business uses together with open areas, all designed as an overall community; and a walkable community, giving priority to people rather than to cars.

According to its own literature, it was "planned to challenge the town planning trends and policies of the 20th century that led to isolated housing estates and shopping centres far from places of work and leisure, forcing ever greater reliance on the car." Providing local employment was critical to that plan, and the 2019 Poundbury Factsheet states it provides employment for "some 2,306 people in 207 shops, cafes, offices and factories, with a further 557 employed in construction across the site and many more self-employed or working from home."

The Poundbury masterplan aimed for one job per house, but there is a higher rate than that. However, while the imagined idea was that people would live and work in Poundbury, what has actually happened is that many people commute in or out of Poundbury for work.

Businesses from Dorchester have moved into Poundbury and many of those who work in Poundbury do not live there. Perhaps as an extension of Dorchester that technically meets its remit, but not quite in the imagined village lifestyle. As for cars, there are still a lot of them. According to the 2021 census, 8 out of 10 households in Poundbury have a car, though this falls well below the national average of 12 cars for every 10 households in England.

As a visitor and in photographs, there is a feeling that cars are everywhere, perhaps because there are no parking restrictions in Poundbury. As a result, according to the Dorset Echo, commuters into Dorchester are parking in Poundbury and catching the bus or walking the last 20 minutes into town.

Feeling Poundbury

In keeping with New Urbanist principles, connectivity and mixed-use development are central to Poundbury’s design. Rather than being based around a central node, Poundbury is based on the idea of different areas merging into one. There is no village green or town square but a series of smaller squares or "hubs", each with its own distinct character and identity.

Pummery Square is the hub of Phase One, the Buttermarket the hub of Phase Two and Queen Mother Square is the hub of Phases Three and Four. Shops are scattered and interspersed with houses, and sometimes industrial units. Streets are connected to others through small alleyways leading to garages, courtyards, and parking areas. This creates a somewhat disorienting feel when you walk around - higgledy-piggledy streets leaving you disoriented in space, buildings that seem to bear no connection to one another architecturally, leaving you disoriented in time.

This disorientation is deliberate - an attempt at replicating the kind of organic chaos that longevity of place and habitancy often creates. As the Duchy Estates development manager for Poundbury, Jason Bowerman, commented when I spoke to him, "An area of this size might have taken 200 or 300 years to actually evolve. Over that time you would have had different community elements that would have been established. Some would have failed but they would have been replaced by others. You’d have ended up with quite an eclectic mix of different community ventures and, likewise, with architecture; you’d have that mix, it wouldn’t have all been uniform."

The attempt to create a feeling of longevity informs design elements throughout the area. The newly opened Jubilee Hall incorporates four iron pillars salvaged from the Victorian Jubilee Hall in Weymouth, demolished in 1980. An obelisk on the outskirts is a replica of one in Dorchester erected in 1787. Because of Dorchester’s twinning with Bayeux in France, replicas of the Bayeux tapestry, unveiled in 2018, hang in Brownsword Hall, itself reflecting rural town hall design from centuries ago. While such features seem contrived, they reference New Urbanism’s desire to create architecture that harmonises with its surroundings and connects to the past.

Poundbury integrates old with new in ways almost undetectable to the average citizen – albeit obvious to built environment professionals who can easily identify modern construction, Frankenstein styles, botched symmetry and altered proportions

The dizzying array of architectural styles disguises the way New Poundbury incorporates pre-existing features of both the landscape and Dorchester’s urbanity in its design, integrating old with new in ways that make it almost undetectable to the average citizen - albeit obvious to architects, architectural critics and built environment professionals who can easily identify modern construction, Frankenstein styles, botched symmetry and altered proportions.

The only straight road in Poundbury is the Bridport Road, which used to be the main road out of Dorchester to the west. Along this road are a handful of houses that were there before the development was started, but unless you were told this, you wouldn’t necessarily know. Poundbury Farmhouse, which now contains the Duchy offices, and the garden centre, Poundbury Gardens, were part of a working farm for generations. Indeed, there is a long and ancient history to Poundbury.

“The higgledy-piggledy streets leaving you disoriented in space, buildings that seem to bear no connection to one another architecturally, leaving you disoriented in time. This disorientation is deliberate - an attempt at replicating the kind of organic chaos that longevity of place and habitancy often creates”

The Iron Age hillfort of Maiden Castle, which lies to the south of Poundbury, dates back to 600 BCE, and Bronze Age burials suggest inhabitation from at least 2000 BCE. In the north, a Roman camp dates to around 43-410 CE, and excavations have unearthed neolithic flints, meaning humans were working or moving through the area as long as 6,000 years ago.

More recently, during the First World War, German prisoners of war were held at Poundbury ca,p, an artillery barracks on the Poundbury road on the outskirts of Dorchester. The area has been in continuous use and reuse.

In its reimagining, past and present are united and intertwined with cultural meanings that blur temporal boundaries. Having been built in a short amount of time, this blurring of timespan makes it challenging for Poundbury to create community with a sense of belonging and place.

The masterplan

In aiming to design not only architecture, but also community, the theory of Poundbury was that it was only through meticulous planning and management at every stage of such a development that the community transformation it envisaged could be achieved. This ambition went beyond architecture and construction to overseeing the establishment and maintenance of community groups once people moved in. There are aspects of Poundbury where minute management has been integral.

The development of the Great Field, for example, was only possible because of careful planning, management and resources. And every person I spoke to loves the Great Field - a vast and slightly windswept area, with rolling undulations, wild areas, an extensive playpark including scaled-down models of Poundbury buildings, and a central community cafe.

Five years ago, the Great Field was a field of oil seed rape. It has been transformed, under the skilful eye of Miles King, chief executive of conservationist organisation People Need Nature. Only with planning, care, management - and money - can something like this be achieved.

The problem with the masterplan, however, is that it provides little room for evolution. Britain 2022 is a very different place to the Britain of the late 1980s and early 1990s when Poundbury was planned and the masterplan does not reflect the needs of contemporary living for many. Garages built in the earliest phases are too small for the cars of today. The housing configuration is of a bygone era - separate rooms with different functions, living rooms on the first floor, front doors that open straight into halls and stairs, back doors into the kitchen, with nowhere to take off muddy boots, for example, or wipe a dog's feet.

In addition, the masterplan failed to foresee the consequences of some of the design choices. When hit by heavy rain, the gravel laid on the paths washes into the drains and blocks them. As for the mixed demographic population that the masterplan aimed for, that is open to question.

The high cost of private housing in Poundbury excludes many people from buying there, and the choice of amenities and shops makes it clear which demographics are being targeted - the main supermarket is a Waitrose, interior design shops are prominent among the retail clusters, and there are numerous wealth management organisations, all within this small urban extension. While these shops are selling to the wider Dorchester area, having them together in Poundbury creates a particular aura. A hot chocolate in the Honeybee Cafe cost over £5.

That said, 35 per cent of Poundbury's properties are designated as affordable housing - a mixture of rented properties, sheltered accommodation, shared ownership and discounted open market sale. According to the 2021 census, 38 per cent of residents live in rental accommodation, broken down as 21 per cent social rent and 17 per cent private rent.

Six housing associations manage a number of these properties, all of which are created tenure blind, scattered among the privately owned and rented houses; an attempt to create social mixing and cohesion. This is welcomed by those living in the area, who agree with the ethos of mixed living (indeed, it was mentioned that when someone made a negative comment about social housing at a residents' meeting one year, they were unanimously booed).

But while tenure blind in principle, at a Dorchester planning committee meeting in 2019, it was noted that some of the new affordable houses being developed were smaller than the national recommended size. Although many residents live in rental accommodation, the people I spoke to felt that people moving to Poundbury were interested in making a long-term home there, rather than seeing it as a place of transition.This can be both positive and negative depending on your position.

Tue Ahmad and his family, who have been renting a home there since 2021, have found it harder to integrate: "It's very tight-knit around here, with an older demographic, and people don't move a lot” he says, "so moving here was ... different to where we've lived before."

According to the 2021 census, of the 4,067 inhabitants of Poundbury, the demographic is older than average, with 33 per cent of the population aged over 65. In addition, 93 per cent of the population was born in the UK and 94 per cent identify as White British.

Poundbury is also quiet. This is part of its appeal to some, and the opposite for others. While lights are on in houses at night, there were few people on the streets and, to me, the place felt somewhat empty. Even during the day, nowhere was noticeably busy save for three exceptions: the Great Field, next to Darners First School when it opens and when it lets out, and the Waitrose and garden centre on Queen Mother Square.

Ahmad feels this too. "I used to walk around and I'd take lots of pictures and share them with friends. The pictures feel spooky; there's nobody in them so it does feel very desolated."

“The nine-metre obelisk, a neoclassical bus shelter, a fountain in a car park… There's a little-used petanque court at the edge of the Centenary Field, which looks as though it's been thrown out of a window to land there. All of this makes Poundbury feel strange. Ahmad describes it as feeling "dislocated; like you're living in a bit of a stage set"

I ask him why he thinks this might be: "Things sell here very, very, quickly so they're not empty, he says. "I just think they're living differently." That feeling of difference - an otherworldliness - is furthered by the architectural layout and not just the juxtaposition of different styles but also the placement of follies and monuments. The nine-metre obelisk, a neoclassical bus shelter, a fountain in a car park.

In 2022, wooden steps were built into a hill on the Great Field, creating what looks like an amphitheatre that looks onto three large trees. There's a little-used petanque court at the edge of the Centenary Field, which looks as though it's been thrown out of a window to land there. All of this makes Poundbury feel strange. Ahmad describes it as feeling "dislocated; like you're living in a bit of a stage set". Tarling calls it "surreal".

Not everyone agrees. Mumford moved to Poundbury when she was 22 because of its uniqueness. Growing up in Dorchester, she had always been aware of its development, and wanted to be part of it. "It was a new and upcoming development that really excited me." she says. "Having lived in Dorchester for 12 years, Poundbury was a new fresh burst of life and energy."'

"I saw King Charles outside my house a couple of months ago," she says. "Things like that are exciting. It's great to just randomly see a royal walking down the street"

Pass the Duchy

The Royal connection to Poundbury' cannot be ignored. It is part of what has drawn media attention - as well as derision – to the project. Indeed, the connection is stamped all over the area, with the coat of arms appearing on lampposts, parking signs and bollards. The development is on land originally owned by the Duchy of Cornwall – a Duchy dating back to the 14th century when needing an income stream for Prince Edward (known as the Black Prince), Edward III converted the Earldom of Cornwall into a Duchy, including within that a hereditary title and landed estate now totalling around 21,000 hectares (53,000 acres) across 23 counties, mostly in south-west England.

The Duchy's offices are in Poundbury Farmhouse, one of the area's few original buildings. The enormous square at the top of Poundbury is Queen Mother Square. Central to its vista is a domineering statue of the Queen Mother. Several roads are named after racehorses belonging to the late queen. The latest area of development is Crown Square. While this relationship to the crown has been the cause of some disdain, the residents and business owners are more ambivalent.

Mumford enjoys it: "I saw King Charles outside my house a couple of months ago," she says. "Things like that are exciting. It's great to just randomly see a royal walking down the street." Mumord tells me Charles is supportive of the businesses and the community in general.

Ahmad feels that because of the vested interest, and the resources available to the Duchy, the quality of the development and the attention to architectural detailing is much better than most new builds. "I wanted to hate it because it was Charles” he says. "But after living here, I feel more ambivalent."

Until his accession to the throne last year, Charles was personally involved in Poundbury's development. The Duchy has now passed to William. Whether this will change the development of Poundbury is yet to be seen. Bowerman does not foresee any great changes; but rather an ongoing commitment to the area and its community. Many of the residents, however, are hopeful for change.

Charles was interested in urbanism and the potential to maintain "Britishness" through new development. Because of his younger age, William is seen as being more progressive and more in touch with contemporary needs. What is clear is that the Duchy will remain involved. While the intention might have been to eventually hand over the majority of elections to local community groups, Poundbury will never be completely independent. Many of the houses have been sold with their freehold, but the Duchy retains interests in Poundbury, including several businesses, long-lease and directly let dwellings and most of the communal areas of land. As part of the masterplan, it oversees not only the completion of its development but also the ongoing aesthetic of the area.

This can cause tension. Although they own the freeholds, residents have to apply to the Duchy to make changes to their properties, whether to paint their front door in a different colour or install solar panels on their roofs. Until they are adopted by Dorset Council, the roads belong to the Duchy too.

How walkable is it?

Charles' architectural vision was of urban "villages" - urbanism that reflected aspects of village life, such as walkability, mixed-age demographics and living and leisure in one place. Creating spaces like this, he thought, would recreate community and identity, which he felt was being eroded in 1980s Britain. Walkability was an aspect that everyone mentioned as a positive of Poundbury, whether they lived there or not.

"Everything's so walkable. I'm really lucky - everything's on my doorstep. I don't need to go out of Poundbury now, everything I need is here. I'm spoilt for choice"

Poundbury is small and has most of the facilities you need for life: doctors, dentists, a supermarket, butchers, deli, hairdressers, cafes, restaurants, two pubs, a post office, various shops and an undertaker too. Chris, who moved to Poundbury in 2016 with her partner Mike, comments: "Everything's quite handy. You can walk to most of the things that you might need. You can walk to the doctor's, which is the other side of the field. You can walk to the dentist, which is there on Bridport Rd. The hospital's down the road. It's a good location." Mumford notes the same: "Everything's so walkable. I'm really lucky - everything's on my doorstep. I don't need to go out of Poundbury now, everything I need is here. I'm spoilt for choice."

It is amenable to walking for various ages and interests: The Brownsword Hall is used by a variety of community groups, hosting toddler groups, book clubs, exercise classes, quiz nights and jazz evenings. There is a Poundbury Rotary club, an active Art Society, wine clubs, and more. The Great Field has a children's playground, running tracks and plenty of space for walking, reading and having picnics in the summer. Two Park Runs use Poundbury’s green spaces, bringing in people from across Dorchester.

But walkability is not only about size, it also relates to organisation and accessibility. As I walked about, I had to keep crossing the road because the pavement had ended. In some areas there is no pavement at all, meaning I had to step in to the road. There is gravel scattered across most of the paths, and very few dropped curbs. The shops are scattered around in different areas with very few clustered together. This limits 'walkability' to people with time to spare and those without mobility issues who use wheelchairs, push buggies, or have kids on scooters, for example. In some areas there is no pavement at all, meaning I had to step in to the road. There is gravel scattered across most of the paths, and very few dropped curbs.

Walkability is not only about size, it also relates to organisation and accessibility. As I walked about, I had to keep crossing the road because the pavement had ended... It seems apparent that a woman has not been involved in the design

It is clear that the mixed population imagined for Poundbury did not include mixed agility. In 2019, the Royal National Institute for the Blind expressed their concerns "with the general accessibility of Poundbury's streets for blind and partially sighted people, including shared space areas across the town." In particular, the RNIB mentions the shared surface areas on Queen Mother Square in Poundbury as part of its national campaign against shared space design in general. Shared spaces are paved areas with no detectable curb or clearly defined pedestrian crossings, meaning "blind and partially sighted pedestrians are left with no way of knowing where the pavement ends and where the road begins, and when to cross the road safely."

Shared spaces, once thought to make roads safer, offer a sense of free-for-all on the roads due to a lack of markings - a design choice also made to avoid clutter in the forms of signs and over painting. The result is no right of way at any junction. The coroner identified the lack of roadway markings and parking restrictions as playing a crucial part in the death of Richard Hallett, aged 25, who was knocked off his motorbike and killed at a junction in Poundbury in 2018.

The coroner asked that road markings and parking restrictions be introduced, "to prevent future deaths." But this hasn't happened, with a rejection of Hallett's mother's petition to paint yellow lines at the road junction.

The coroner identified the lack of roadway markings and parking restrictions as playing a crucial part in the death of Richard Hallett, aged 25, who was knocked off his motorbike and killed at a junction in Poundbury in 2018

The layout restricts walkability in other ways. Tarling's teenagers have friends in Poundbury, and they like to spend time on The Great Field. But they don't like to be in the town at night. "There's a lot of dark alleyways and they feel quite unsafe. [The teenagers] won't walk around much at night at all. You'll get a little alleyway into a parking area, which is just garages and stuff.”

When I visited from London, I arrived in the dark and walked alone through the unusual street layout, aware of how quiet it was. There was no possibility of rounding back on yourself and finding a brightly lit area full of people. It seems apparent that a woman has not been involved in the design.

Several people questioned the Duchy's claims to sustainability and eco-credentials, and highlighted the hypocrisy given media stories of Charles having solar panels on his homes. "In the beginning all the media was about Charles' eco-village, right?" commented Mike. "But now they've dropped that marketing”

Those who live in Poundbury, however, tell me they feel safe, including all genders and ages. Tom Amery, Managing Director of the Watercress Company, who owns the Brace of Butchers, commented: "Visitors are often confused, partly due to the layout, as they can find themselves lost, but once you get to know your way around it all makes perfect sense. It's like nothing many have seen."

Mumford told me she feels very safe walking around. For her, the feeling of safety comes from its small scale, but also from the established community she is part of in Poundbury.

Eco-credentials and sustainability

Part of the design was centred on sustainability. When it was first being planned, the aim was for Poundbury to be sustainable as a living, working and leisure space, with as little impact on the environment as possible. This focus is evident across the development. The Great Field has three different wildflower areas, and in the summer the grass is allowed to grow tall with only certain paths and areas for picnics mown, to encourage wildlife and biodiversity in the area. A dug-out sump catches rain run-off, the sustainable urban drainage providing a 'natural' flood protection area. There are nesting boxes for swifts and other birds, created in partnership with the RSPB, thousands of trees and plants have been added, and ongoing care is taken to all of these aspects. A walled garden provides space for growing food.

As well as informing the planted areas, sustainability, along with other principles of New Urbanism, including traditionalism, informed many of the design choices of Poundbury, such as the use of timber for all windows and doors. There has been media coverage on resident opposition to the mandatory use of wooden windows, with complaints that current windows are draughty, poorly made, require maintenance or were built in softwood, rather than hardwood. In some areas of Poundbury, you can see rotting frames, and a group has arisen calling for permission to install UPVC windows that has received local press. The installation of solar panels has become an area of contention. Along with clothes dryers and bins, PV panels may not be visible from the street and require consent to install. More than one resident has had their recent application to install solar panels on their house rejected, under the reasoning that it would interfere with external sightlines.

Several people questioned the Duchy's claims to sustainability and ecocredentials, and highlighted the hypocrisy given media stories of Charles having solar panels on his homes. "In the beginning all the media was about Charles' eco-village, right?" commented Mike. "But now they've dropped that marketing”.

When I asked the Duchy's development manager about this, he refuted the claims that applications for solar panels are being rejected: "There will be times when we won't be able to approve, but wherever possible we would like to be able to .... With evolving materials such as solar slate, I think increasingly there will be opportunities to [install solar panels], even in areas which are difficult now."

In 2012, the UK's first anaerobic digestion and biomethane-to-grid plant was built on a Duchy farm just outside Poundbury. According to Barrow Green Gas website, the plant will provide enough gas for 4,800 homes and spread through the distribution network to 6,000 homes in mid-winter and 88,000 homes in mid-summer. It also produces the biproducts of carbon dioxide (sold to the food and drinks industry) and a soil conditioner (sold for agricultural use on farms). The digestor is fed on grass and maize grown on local farms, including some on Duchy land. One person I interviewed asked whether its environmental credentials are diminished if what is being digested is grown specifically for that purpose.

Jason Bowerman told me that keeping up with technological advances and reflecting the very rapid changes in environmental considerations and materials has been an important objective for Poundbury. "It's a continually changing target, but with modern technology it's becoming far more possible. A big part of what we do is keeping a watch on what's available, and an open mind on technology," Bowerman said.

Community building

Much urban development of our century positions placemaking and community creation at its core. This comes from the belief that communities are lacking and losing identity in most urban development. Yet there is a strong identity to each area and its people. You only need to look at the mutual aid and community groups thriving on social media to see that identity is strong, and looking back on lockdown, it is obvious that community is too.

Rather than falling apart, during the Covid pandemic, people came together to look after one another, and most of these groups were organised around streets or places. The premise of community, however, is integral to much of Poundbury's design and masterplan. The scattered shops aim to create places where people intersect. Specific types of community groups were set up and overseen by the Duchy – the Residents' Association for example – with an aim for these to become self-sustaining in creating community.

As Austin Williams pointed out in 2008, this is a particularly patriarchal approach to community development: one that sees a duty of intervention not only in urban design, but also in social manipulation. As he notes, the community of such imagination is not diverse or inclusionary – it is actually built on a premise of exclusion of particular types of people: teenagers, for example, the visible presence of whom is seen by some as marker of a bad area, but in reality reflects a vibrant and dynamic community of age and interest.

Is there a feeling of community in Poundbury? Like anywhere it depends on who you speak to. Mumford says there definitely is. She feels Poundbury is a warm and supportive place, particularly among the business community. Mike and Chris, who have lived there a similar amount of time, have found it more of a challenge. "Most of the people we come across [in owner-occupied houses] are not from Dorset or Dorchester. They are eager to make friends, but it can be difficult. You have to build a whole new community if everybody's coming in,” Chris commented.

Ahmad told me that he and his family have found it harder to connect than where they lived before: "There's not a real soul, no sense of family and families mixing together here. So I feel like it's a bit distant, a bit cold and isolated." Rob Owen and Ben Black, meanwhile, who run the Brace of Butchers, said they feel very much a part of a vibrant and supportive community that includes people from all socio-economic backgrounds. "It reminds me of growing up as a kid in Liverpool, where people would say hello to you as you walked down the street. There's a community feeling to it, like I feel like you could knock on the door of anyone if you need something," Owen told me.

Gill, who lives in Old Poundbury, feels like New Poundbury is exclusionary, and this is something she wishes that could change. "I think it's a shame that we can't all be one Poundbury. I would love there to be more integration, rather than a kind of them and us situation, which is sad. I think it's a wasted opportunity - it's all the same place - Poundbury."

As for my visit, while I found the architecture and layout strange, the people were warm and welcoming, going out of their way to try and help me. Like many places, the community of Poundbury came together during the lockdowns of recent years. This is starting to dissipate, with people going back to their busy pre-pandemic lives and different communities of interest. What that tells us is not that community doesn't exist, but that life makes community.

Community is not created through architecture, although, of course, good design can help make places where people want to live, work, and spend their time. This is starting to be seen in Poundbury. Land has recently been given over to Transition Town Dorset, which has created a community garden, planted an orchard, and keeps ducks and chickens. The land it manages is wild and messy. It looks free compared to the manicured aspects of other parts of Poundbury. In the Southern quadrant, the first part to be developed, there is moss on the roads. Mole hills are being created in Centenary Fields. Nature is starting to push back against culture. Residents are also finding ways to resist the control of the masterplan.

Walking around Poundbury I noticed several houses where identity was being asserted: tumbling plants in numerous planters; the allotments. Only time will allow this to expand in Poundbury, and only if it is allowed to, on its own terms, not dictated by a masterplan made over 30 years ago.

The idealised community and identity that underlies the masterplan could never actually exist. Like Poundbury itself, it is somewhat mythological. That is not to say there is no community in Poundbury, indeed, there are multiple communities within the plethora of groups and events – art and food fairs, fun runs, charities.

Community is created through shared time, interests, and most importantly people. It cannot be created or managed, but can only happen organically. In this, individuality emerges.

Caroline Bennett is Lecturer in Social Anthropology at the University of Sussex, UK.

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238