Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

The war on trees: “You don't have to be a raging environmentalist to see this is not right”

First Sheffield, then Plymouth, now Cambridgeshire: The battle to save urban trees is raging. The benefits of urban forests are well known, from carbon capture to crime reduction, so why are councils still cutting them down? Ella Jessel reports

M ore than 100 trees in central Plymouth were cut down last month under cover of darkness. Contractors set to work behind tall fences as police and security guards patrolled the site.

The so-called “midnight massacre” on the South coast was halted at 1am when local campaigners managed to obtain a court injunction. Yet it came too late for 110 trees. Come morning, fallen trunks lay in piles along the street.

This mass-felling came just hours after the council greenlit plans to progress with a £12.7 million “urban park”. It was a decision rushed through ahead of local elections and the start of bird nesting season.

“It was shocking”, says Alison White, founder of Save the Trees of Armada Way (STRAW), the campaign which secured the injunction. “I never expected they would do something like that.”

“While everything else declines, a tree gains value as it as it grows”

“We were, and indeed are, upset at both the scale of the tree felling in Plymouth city centre and the use of nighttime operations to do this,” a spokesperson from the Woodland Trust said. “The retention of existing trees should be a priority for consideration for the approval and funding of the scheme, not least because we’re in the middle of a climate and nature crisis.”

With cooling canopies and the ability to absorb tons of carbon, mature trees play an important role in helping fight climate change. They have a host of other benefits, and have even been shown to make people happier.

But across the country majestic trees are being felled to make way for new highway projects, buildings or infrastructure. With little legal protections, local people resort to protest to stop the saws. In 2018, one vicar chained herself to a century-old plane tree being removed for high-speed rail line HS2.

In light of the felling fiascos, do trees need greater protection? The Woodland Trust has called for trees to be treated more like historic buildings, with a dedicated body to safeguard them.

One solution could be giving all trees a TPO as standard

“We’ve currently got a campaign called Living Legends running to convince government to strengthen policy protection so that trees everywhere can grow old safe from harm. That’s whether they’re in new developments, urban areas or the countryside,” a spokesperson from the Woodland Trust said.

The Woodland Trust is also calling for reforms to the existing Tree Preservation Orders (TPO) system. These orders prevent a tree from being cut down but can only be issued by a local authority, presenting a problem if it’s the council that wants to lop the tree down. “We’d like to see changes made such as widening the circumstances when they can be used and also stronger deterrents to felling trees with Preservation Orders.”

One solution could be giving all trees a TPO as standard, says architect Sue James, founder of the Tree Design Action Group (TDAG), a cross-sector group promoting the role of urban trees. That’s an option currently being looked at by Belfast City Council.

White agrees, adding: “We shouldn’t be having to campaign and make a case to save a tree. The council should be making the case to lose one.”

However giving trees more protection will in turn require more enforcement, and councils are so cash-strapped some have even stopped employing tree officers.

American research has found that city trees in a public right-of-way are associated with a significant reduction in violent and property crime

Tree cutting is unpopular and these conflicts can leave lasting damage on communities. Just days before Plymouth’s clandestine operation, a damning report was published into Sheffield’s infamous tree-felling saga that sparked protests back in 2013, described by the Woodland Trust as a “very dark time in the history of the city.”

Yet, from the lime trees of Wellingborough, Northamptonshire to the plane trees of Euston Square, from Bournemouth’s pine trees to the soon-to-be-felled 500 apple trees of Greater Cambridgeshire’s Coton Orchard, the slaughter continues. Why aren’t lessons being learned?

In Plymouth, the council felled the trees on Armada Way to deliver a new 1km-long “linear park”, a project in the works since 2017. The scheme aims to smarten up the area around a 1980s shopping centre and create a “tree-lined boulevard” designed by Studio Agora.

The new route will carve out a walkway from the city centre to the sea, inspired by the “grand axis” in the original post-war ‘Plan for Plymouth’. Unusually for such a large scheme, which will also introduce a sustainable urban drainage system, a cycle lane and new play areas, the council is delivering it under permitted development for a public highway.

The project has support from some quarters, including the local city centre Business Improvement District, which argues the existing tree cover encourages anti-social behaviour and makes it “impossible” to provide CCTV surveillance. However American research into urban vegetation has found that trees in a public right-of-way and green space in general are associated with a significant reduction in violent and property crime. The strongest positive predictor of violent crime in cities is not tree cover, but social disadvantage.

In Plymouth, the council knew the plan to axe 129 mature trees was unpopular long before the chainsaw massacre. Plymouth City Council admitted its consultation revealed “overwhelming” opposition to the scheme, with 68% of people opposed and just 16% in favour.

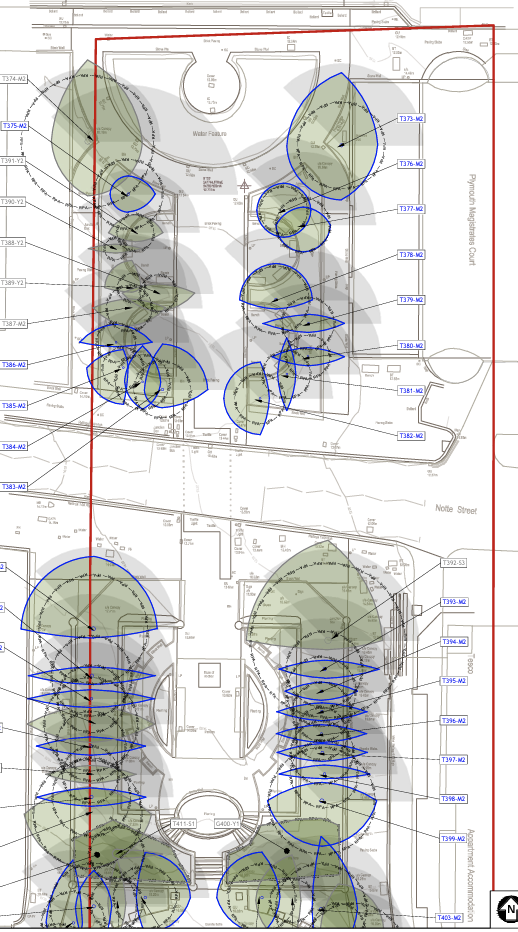

Yet it ploughed on, saying its surveys had shown the existing trees on Armada Way were in “varying condition” with many near end of life, planted too close to buildings and that the species were considered “wrong tree, wrong place”. However, the city centre tree survey, which is available online, identified just 21 trees as “unsuitable for retention” out of 487 trees, with the majority of those in Armada Way designated as High Quality or Moderate Quality, known as Category A and B, respectively.

Plymouth City Council declined to comment when approached. However Martin Ivatt, City Centre Regeneration Coordinator for Plymouth commented on LinkedIn that there were 11 Category U trees recommended for removal in Armada Way. “The others are Cat B or C, but many have issues which go beyond that categorisation system, eg. proximity to buildings, damage to buildings or footway, the historic vista, inability to provide the comprehensive sustainable drainage system infrastructure underground.”

Information on the local authority’s website shows plans that include planting 129 new trees in orderly lines along the boulevard with a new paved central walking path and fountain. Ivatt says the park has a “huge raft of other enhancements, including restoring the historic vista to the Hoe which was the whole purpose of the corridor.”

White says the old trees simply did not fit with the new vision. “We would never say keep every single mature tree and would be happy to lose a few if they were in poor condition. But if it’s not essential, it’s completely bonkers.”

“They disregarded our views because they think we’re scruffy tree-huggers”, she says, adding: “But you don’t have to be a raging environmentalist to see something like this is not right.”

The Business Improvement District argues the existing tree cover encourages anti-social behaviour and makes it “impossible” to provide CCTV surveillance

“The local community has for some time been expressing their opposition to the council’s plan, not least through the STRAW campaign,” a spokesperson from the Woodland Trust said. “We have written to the leaders of the four main parties in Plymouth urging whoever leads the council after the elections in May to ensure the remaining mature trees are incorporated within the scheme design in a way that ensures their long term retention – for their direct benefit and as a symbol of the importance of our urban trees.”

The replacement of existing trees with newly planted ones is not carbon equivalent, however. According to TDAG, it can take at least 25 years for a new tree to match the benefits of an existing one.

“We shouldn’t be having to campaign and make a case to save a tree. The council should be making the case to lose one.”

Meanwhile the Devon Wildlife Trust has pointed out that while 30-year-old trees might not look like “perfect specimens”, they likely support lichens, fungi, mosses, insects and a range of other species. New trees do not support such biodiversity, and as The Developer has recently reported, have a shockingly high failure rate.

“It is disappointing that a planning authority is pursuing this approach of undervaluing the existing nature we have,” the Trust said, pointing out it was at odds with the council’s net zero goals and the commitments in its own 2019 Tree Plan.

“A one-for-one replacement doesn’t work mathematically”, adds Kenton Rogers, a forestry consultant and co-founder of social enterprise Treeconomics. “Even a large and expensive new tree of around 6-8 inches in diameter will only have a crown of 1 square metre”.

Trees begin to “pay us back” when they reach about 30 years old and their canopies grow and spread, says Rogers. Unfortunately, this is the point many urban trees are cut down.

In Plymouth, the felling scandal hit national headlines, and was branded “environmental vandalism” by the local MP. In the ensuing chaos, Conservative council leader Richard Bingley resigned.

It’s a familiar story. Just days before Plymouth ordered in the chainsaws, Sir Mark Lowcock’s report was released into Sheffield’s “dark episode” of tree felling. It found a range of failures by the city council and its contractor Amey who together removed around 5,000 trees as part of the £2bn Streets Ahead programme.

Lowcock found the authority had misled the public, an independent tree panel it had set up, as well as the courts. The report also revealed that at the peak of the dispute, councillors even suggested resorting to killing healthy trees by stripping off bark to "defeat" protesters.

Describing evidence of a “bunker mentality” within Sheffield council, Lowcock wrote: “The Inquiry’s view is that the council was significantly motivated simply by the determination to have its way.”

“Trees need to be considered as an integral and critical part of urban infrastructure”

According to Rogers, these conflicts show an urgent need to change the “top down” way trees are dealt with. People in both Sheffield and Plymouth felt “completely disenfranchised”, leading to deep divisions and both sides taking up entrenched positions, he says.

Sheffield council and Amey have both apologised for failings over the felling dispute, and in 2021 the city embarked on a “new chapter” with the launch of the Sheffield Street Tree Partnership.

The partnership is pursuing a more collaborative approach and introduced volunteer street tree wardens who now patrol a local patch. If the council wants to fell a tree it now runs an individual consultation via an online hub to allow local people to challenge the decision.

National planning policy is increasingly pushing for more trees in new developments, with the new NPPF requiring “tree-lined streets” on all new schemes.

Rogers says some developers are “forward-thinking” and name checks Urban & Civic for its progressive approach to trees on its large mixed-use scheme in Cambridgeshire. Yet most developers, he says, still see trees as “cost centres”.

TDAG has produced a guide for developers on how to approach urban trees, with retention one of its key principles. “Trees need to be considered as an integral and critical part of urban infrastructure”, says architect Sue James, TDAG’s founder. “While everything else declines and will lead to replacements, a tree gains value as it as it grows.”

Giving trees more protection will require more enforcement when some cash-strapped councils have eliminated tree officers

Another of TDAG’s key asks is that every council in the UK has a tree strategy adopted as part of its Local Plan setting out plans for protecting and enhancing urban forests. According to The Tree Council, currently only around 50 authorities have such a strategy in place.

But some are strides ahead. The UK has 19 cities that have received ‘Tree City of the World’ status for their commitment to urban forestry including Birmingham, a city with 1 million trees. It has completed an urban forest masterplan, the first of its kind in the UK.

Meanwhile Wycombe District Council has pioneered a new “canopy cover” policy and since 2019 has required developers to retain or enhance a site’s existing tree cover.

If they catch on, these models could provide a blueprint for a new approach to street trees.

Back in Plymouth, campaigners are steeling themselves for a legal battle, where the focus is on keeping Armada Way’s remaining trees – and stumps – in the ground. White says: “Hopefully this will send a bit of a warning to other councils.”

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238